The mid-late 90’s spawned the immersive sim, a genre defined by influential PC titles such as Thief: The Dark Project and System Shock with the original Deus Ex following suit at the start of the millenium. Ion Storm and Looking Glass Studios pioneered the open-ended design we currently associate the genre with–design that consists of two core tenets:

- Large interconnected environments

- Player expression

The first principle is simple. An immersive sim generally consists of either one large open world map or several self-contained levels. Each environment in an immersive sim must provide a sense of scale on a micro or macro level while facilitating multiple playstyles. These playstyles are usually given more weight through some sort of progression system. Regardless of how a player chooses to build their character, proper immersive sims are designed from the ground up to allow each objective to be completed in a multitude of ways.

System Shock 2

Deus Ex: Mankind Divided and Prey are shining examples of this complex genre in an industry so far removed from the creative spark the industry once thrived in. Both these games are laser focused in their approach to game design, providing true freedom without the artificial progression barriers emblematic of contemporary triple-A game design.

Games are not about being told things. If you want to tell people things, write a book or make a movie. Games are dialogues – and dialogue requires both parties to take the floor once in a while – gamesindustry.biz

This creative vision for the medium’s interactivity and its role in shaping unique experiences is the cornerstone of the immersive sim. Industry veteran, Warren Spector’s, sentiment hits even harder nowadays with the seventh and eighth generation of consoles giving rise to some of the most restrictive experiences the industry has known since the introduction of 3D gaming. Franchises that built their legacy on freedom of expression including Interplay’s Fallout have become hollow shells of their former selves.

The mainstream penetration of gaming as an industry has lead to a massive shift in priorities for most Triple-A developers and publishers. That shift chiefly consists of simplifying games to facilitate a new audience. We’ve seen this countless times. Franchises like Thief, Fallout, and The Elder Scrolls that used to mean something have abandoned old school free-form design principles in favor of catering to a broader demographic. It certainly makes sense from a business standpoint. This new audience of gamers didn’t materialize out of thin air and suddenly understand the complexities of yore. They’re being eased in through more and more streamlined entries with each passing year. Unfortunately, the end result is a neglection of the core audience that grew up with some of these intellectual properties.

Child killing in the original Fallout. One of many instances of freedom within a simulation being stripped away further with each passing installment the moment Bethesda took over.

Let’s backpedal a moment to Thief, Fallout, and The Elder Scrolls. Each of these fallen IP’s shares a connection with the modern day reinventions of Deus Ex and Prey. The abhorrent betrayal of the Thief legacy in the form of 2014’s reboot was developed by Eidos Montréal and published by Square Enix–the same duo that gave consumers Deus Ex: Human Revolution and Deus Ex: Mankind Divided. By the same token, Bethesda Studios, the publishing giant’s internal studio, continues to butcher the Fallout and Elder Scrolls names further with each installment.

Despite this sacrilege, Bethesda entrusted Arkane Studios with the 2017 iteration of Prey. As a reboot, it ironically offers more freedom than Bethesda’s own modern open world rpg’s. In an era whereby Bethesda pigeonholes players into playing specific roles for main quests as well as side quests with dialogue responses from NPC’s in select quests remaining exactly the same no matter what you say, a game like Prey shouldn’t even exist.

Yet it’s anomalous existence is a sign that true talent still exists within the Triple-A space. Both Deus Ex: Mankind Divided and Prey explore the genre in slightly different ways, though they each share many of the commandments set by Ion Storm during the development process of the original Deus Ex.

- Problems not Puzzles – It’s an obstacle course, not a jigsaw puzzle. Game situations should make logical sense and solutions should never depend on reading the designer’s mind

- Multiple Solutions – There should always be more than one way to get past a game obstacle. Always. Whether preplanned (weak!), or natural, growing out of the interaction of player abilities and simulation (better!) never say the words “This is where the player does X” about a mission or situation within a mission.

- Pat Your Player on the Back – Random rewards drive players onward. Make sure you reward players regularly and frequently, but unpredictably. And make sure the rewards get more impressive as the game goes on and challenges become more difficult.

- Think 3D – An effective 3D level cannout be laid out on a graph paper. Paper maps may be a good starting point (though even that’s under limited circumstances). A 3D game map must take into account things over the player’s head and under the player’s feet. If there’s no need to look up and down – constantly – make a 2D game!

- Think Interconnected – Maps in a 3D game world feature massive interconnectivity. Tunnels that go direct from Point A to Point B are bad; loops (horizontal and vertical) and areas with multiple entrance and exit points are good.

- Geometry should contribute to gameplay – Whenever possible, show players a goal or destination before they can get there. This encourages players to find the route. The route should include cool stuff the player wants or should force the player through an area he wants to avoid. (The latter is something we don’t want to do too often.) Make sure there’s more than one way to get to all destinations. Dead ends should be avoided unless tactically significant. – gamesindustry.biz

Warren Spector touches on the idea of a simulation when describing the importance of problem solving. This, at the end of the day, is the holy grail of the genre with every other design element serving to reinforce that ideal. Immersive sims are titled as such partly because they are simulations, but not in the sense that you are probably thinking. They don’t concern themselves with ultra realistic depictions of the world “average joe” resides in. Rather, this simulation stems from the concept that the entire game operates by a consistent set of rules and logic. Understanding these rules and remaining true to them is key to maintaining the simulation.

Deus Ex: Mankind Divided

How many games have you played in your life in which a crate can be pushed specifically because a designer decided pushing that crate by that wall was the only way to progress at that point in time? Yet, look around and the rest of the game is littered with crates that can’t be manipulated in any fashion. That inconsistency creates a rift in the simulation. This stands in stark contrast to the consistent game logic in Prey and Mankind Divided, both of which allow players to pick up, place, and throw nearly every object in the game world.

This simulation gives players the tools to experiment and solve logic puzzles in interesting ways. For example, the hub world of Deus Ex: Mankind Divided is filled with verticality, remaining true to the commandment of thinking within a fully 3D space. When navigating the streets, a balcony, fire escape, or even an open window might draw attention. Sure, the player could find several entry points within that building from the ground floor or even below ground level and then exit through that window. However, because the player has grown accustomed to a simulation with consistent logic, the possibilities increase exponentially.

Logic dictates that window is a possible entry point, but Adam Jensen can’t jump high enough to reach it. You know what he can do, though–manipulate objects. A little bit of jerry-rigging together random boxes, trash cans, or whatever else seems like a suitable platform yields an improvised stair case. This isn’t breaking the game or exploiting any systems. It is an example of playing within a simulation to solve a simple logic puzzle. Prey allows the exact same manipulation of physics objects, though it also offers one tool that changes the game in either a dramatic or subtle way depending on how the end user chooses to engage with it–the Gloo Cannon

Prey

Trapping enemies is the gloo cannon’s primary purpose. Directing a stream of munition at a target will harden it into a stone-like substance, allowing the player to damage the enemy with conventional weaponry. The more genius application, however, is its versatility as an aid in environmental traversal. Each shot hardens into a circular glue-like substance when directed at any surface. There is no limit to its use case with none of the invisible walls or insta-death zones modern gamers are all too familiar with.

The turning point for me occured when I came across a power plant-ish area. As per usual, the intricately designed map facilitated upper level access prior to even entering the room. I found a broken walkway that lead to a door. A code I didn’t have access to blocked my entry. Gated behind level 4 security, I was unable to thwart it with my level 3 hacking skill. I had enough neuromods to upgrade to that final level, but I decided to find another way and invest those neuromods into other skills. I explored the upper bounds of the plant to find another door to the room, except this door could only be opened after turning on the plant’s power. If you’re keeping score, that’s already three different ways to access a completely random room in the game.

How did I solve this conundrum? A eureka moment suddenly hit me when I noticed an enemy wandering the room from ground level. I pulled out my trusty gloo cannon and improvised platforms up to the window, allowing me to smash through the glass with a wrench. This was only possible because I solved an unplanned logic puzzle through my own interaction with the game’s systems and underlying simulation.

The rope arrow from the Thief series is another excellent example of the degradation running rampant through the industry. The rope arrow can be used at any contact point on any wooden or mossy surface in Thief: The Dark Project and Thief 2: The Metal Age. That rope’s use case dwindled significantly, with only the designated points on deliberately placed beams deemed acceptable in the reboot. That change alone shatters the entire illusion of an immersive simulation that prioritizes freedom of expression. Thief (2014) is the poster child for how diluted game experiences have become in the past twenty years.

That white area is the only contact point the Thief reboot allows ropes to attach to, a far cry from the older titles.

Mankind Divided‘s intricate design permeates every inch of the experience with even the most nondescript side quests offering a level of freedom Thief (2014) could only dream of. At one point, I was tasked with finding some sort of information from a room within an apartment complex. This locked room, situated on the second floor, enforces that interaction between player and simulation.

Searching for the access code from somewhere in the game world or perhaps even an NPC was within question. Hacking was also an option, though my hacking skill at that point wasn’t high enough. This would have been a barrier put in place by a less ambitious developer to prevent the player from accessing the aforementioned room until later, but as we’ve discussed, artificial progression barriers are antithetical to the immersive sim philosophy.

Prey

Eagle eyed players that canvassed the complex would have found a set of garage doors on ground level gated by lower level security, meaning these could actually be hacked. After entering both garage doors and gathering materials, I found a conspicuous air vent. This vent served as an interconnected tunnel that lead to several rooms within the apartment complex including the previously inaccessible room. The solutions don’t end there, though. If the player invested augmentation points into a strength skill that allows cracks in walls to be destroyed, he/she could have found said crack on the third floor. After crumbling the wall and entering the room, an improvised staircase thanks to the consistent simulation would have allowed the player to enter vents situated near the ceiling–vents that served as yet another entry point to that second floor apartment room.

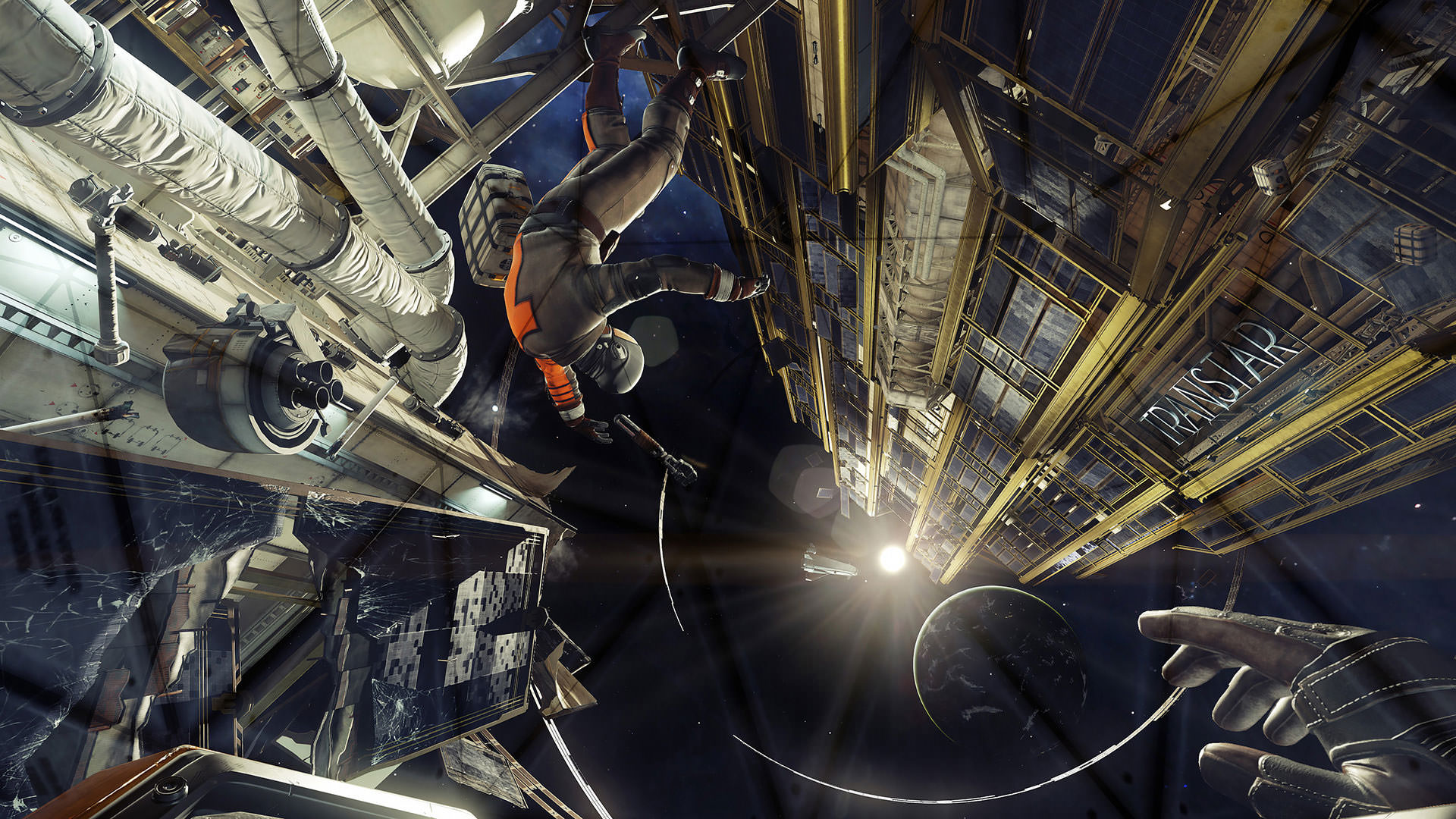

This interconnected nature of Mankind Divided‘s hub world is taken even further with Prey. Whereas Eidos Montréal’s vision consists of two hub locations with individual levels thrown in for good measure, Arkane Studios opts for a single map. The Talos I is a gargantuan space station filled with hundreds of rooms and dozens of floors. The scope of the station is already complex enough to make exclusively indoor exploration feel rewarding with some of the most intricate loops and connections between areas you’ll ever find in gaming. It doesn’t end there, though.

Players are given free reign to exit the station and fly in space within a contained barrier. The only way to enter and exit the station is through five designated air locks. If you choose to exit through Airlock A and find another airlock you want to enter through for more convenient navigation, you’ll need to find and access that airlock from the inside before it can be used as an entrance. That isn’t the whole story, though, seeing as the station is filled with hull breaches and the like. This requires exiting the station and finding said hull breaches to access destroyed rooms that can’t be touched from the inside.

While Square Enix essentially murdered the Deus Ex franchise after Mankind Divided‘s sales figures, there is still hope thanks to Arkane Studios, the final bastions of hope for keeping the immersive sim alive. If you have yet to touch the genre to this day, Prey and Deus Ex: Mankind Divided are perfect modern day interpretations of those design philosophies pioneered in the early days. No genre is as emergent and encapsulating as the immersive sim.